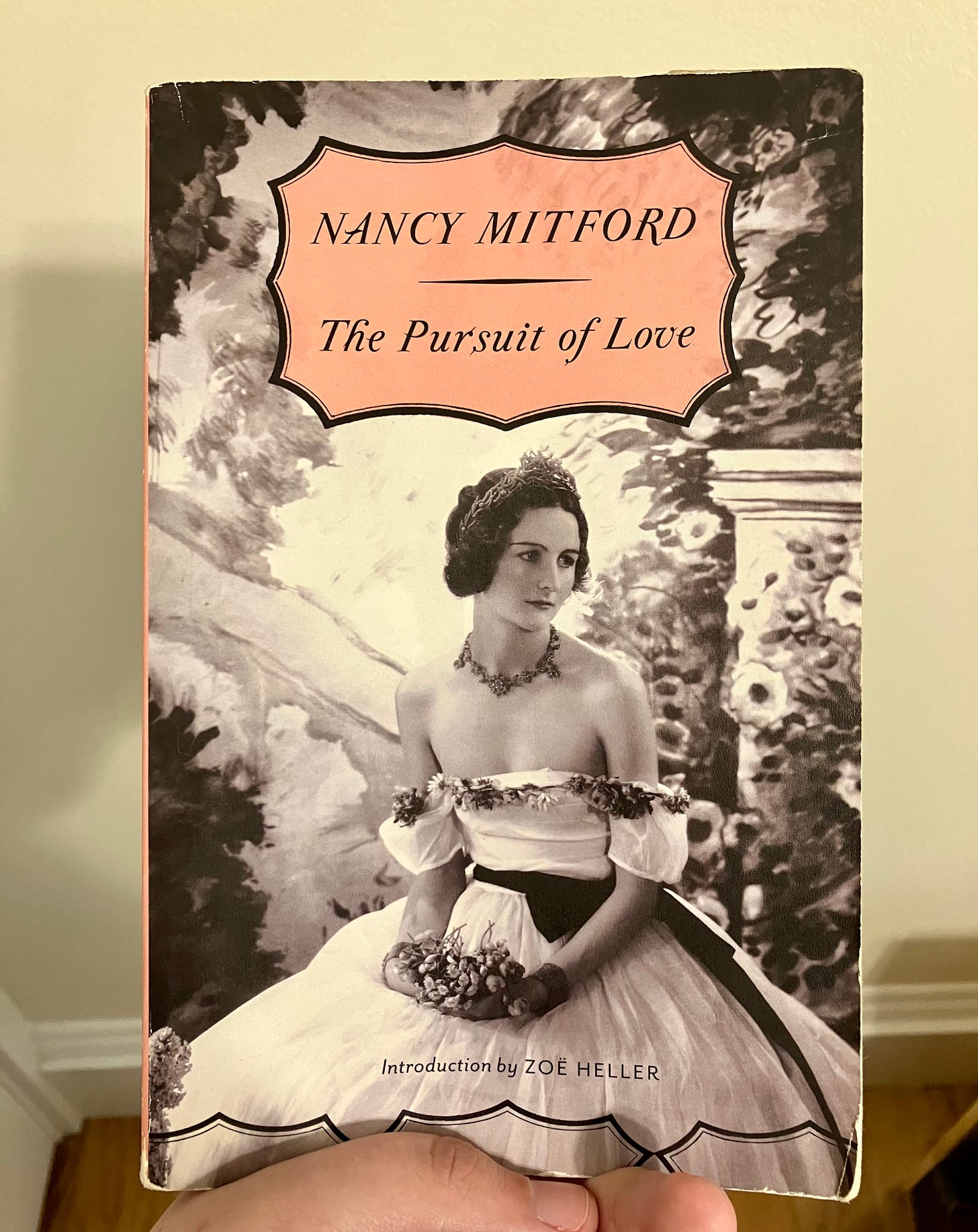

If you have somehow found your way to this newsletter and have not yet experienced the joys of The Pursuit of Love, Nancy’s 1945 novel widely acknowledged as the gateway drug to all things Mitford, 1) ??? and 2) fine, I’ll give you a summary.

This is a novel about the epic highs and lows of the love life of Linda Radlett, an amalgamation of Nancy and her sisters Diana and Debo, who takes up with three very different men over the course of the story, narrated critically by her cousin Fanny. Linda first marries a Tory politician from a dull banking family; she leaves him for a country neighbor’s son, a worldly Communist journalist who soon barely notices she exists; after leaving him with Spanish refugees in Perpignan, she ends up crying on her suitcase in the Gare du Nord and is taken in by a kind Frenchman, Fabrice, who of course turns out to be a wealthy and unmarried duke, and they have a thrilling affair in Paris during the spring and summer of 1939. Because of the inevitable arrival of the war, there is and isn’t a happy ending (though I won’t spoil it here1), depending on whether you believe Fanny’s account of the whole thing.

Beyond Linda, The Pursuit of Love is about the Mitfords’ childhood, and the social habits of the wealthy, and gender roles, and European politics, and what it meant to be English before the war, and friendship, and who knows what all else. It has taken me numerous rereads over the past ten or twelve years to spot and appreciate just these, and it feels silly to say but it really is a book that gives me something new to think about every time.

In rereading this past week for the purposes of my hobbyist publication (tell your friends to subscribe), I decided that The Pursuit of Love is about the fantasy of a good heterosexual marriage, and it was Fanny’s closing assessment of Linda’s life that drove this home to me. Fanny believes that Linda’s adventures leading her to Fabrice were worthwhile, in the end, because she was happy with him, though there is a tinge of jealousy, I think, because though her own husband, Alfred, is perfectly suited for her, she didn’t experience the same passions in meeting and marrying him. We’ll get a bit more of Fanny’s love story in Mitford’s next novel, Love in a Cold Climate (1949)—the two books have always been adapted together for the screen, and all the versions suck, though I will yell about that at some other time—and she seems to like being the wife of a kind, though absentminded, Oxford don.

But even through all that, Fanny’s fantasies about love remain desperately practical and her sympathetic attempt to understand Linda’s choices as the actions of a real person fail because she can only conceptualize passionate love as a thing that happens in stories. For Linda, however, every fantasy must be experienced, not just imagined (guess why we’re reading the novel as told by Fanny, not Linda). While she and Linda are in their late teens, waiting to come out, Fanny remarks that

“we were, of course, both in love, but with people we had never met; Linda with the Prince of Wales, and I with a fat, red-faced middle-aged farmer, whom I sometimes saw riding through Shenley. These loves were strong, and painfully delicious; they occupied all our thoughts, but I think we half realized that they would be superseded in time by real people. They were to keep the house warm, so to speak, for its eventual occupant. What we would never admit was the possibility of lovers after marriage.”

Fanny knows that this happens (her own mother has been married five times, with many partners in between) but after their first ball, when Linda quickly realizes that court circles are exceedingly dull and transfers her attention to the Bright Young Things—real people—she meets at a neighbor’s, Fanny can only think “more than ever of the safe sheltering arms of my Shenley farmer.” Even as she grows up and watches Linda’s affairs from afar, the possibility that fantasies can become reality remains pretty improbable. Of course, given the time and place, it’s not like Linda’s efforts to enact her fantasies are easy or come without significant disruption; there is a reading that says that Fanny’s practicality is much more suited to the actual social world in which she lives and that the novel argues in favor of Fanny’s approach by punishing Linda at the end.

But I think The Pursuit of Love is far more agnostic as to whether Linda’s approach works, and here we must turn to the attitude of its author. In a 1981 forward to the novel, Nancy’s sister Jessica explained that as soon as she finished reading it, she sent a letter to Nancy: “Now Susan,2 we all know you’ve got no imagination, so I can see from yr. book that you are having an affair with a Frenchman. Are you?” Nancy wrote back, “Well, yes, Susan, as a matter of fact I am.”

The Frenchman was Gaston Palewski, an army officer and politician who worked closely with Charles de Gaulle; he and Nancy met when he was posted to London during the war and had a long and intermittent affair that lasted until her death in 1973. Nancy, as we will recall, had been unhappily married to Peter Rodd, and they had separated before the war, though their divorce wasn’t until 1957. Nancy viewed Palewski as the great love of her life, despite how infrequently they saw each other, as well as the fact that at one point while they were nominally together he married another woman and she found out from reading the announcement in the paper.

This act of disloyalty, of course, happened a few decades after The Pursuit of Love was published, and I think it is not unreasonable to say that Linda’s excitement over Fabrice really does reflect Nancy’s excitement over Palewski and a conviction that she too had made her love fantasy come true. Fanny’s practical approach to love and marriage only seems depressing to me because I know how it ended; to Nancy, I’d wager that it was simply about driving home the image of Fanny as Linda’s foil.

Her approach is also depressing because on the teen magazine personality quiz version of The Pursuit of Love, my answers are mostly Fanny’s: I too “feel a priggish satisfaction that I have not grown up unlettered” as Linda and her sisters did; I too wear sensible clothing for my age and station and yet feel strangely dowdy when I look at the other young women around me; I too think that an absentminded and kind Oxford don is the best possible life partner I could hope for. I have had mixed experiences trying to find said don (dating apps are the devil, on both sides of the Atlantic), and as a result it is being harder and harder to hold onto the part of me that sees and approves of seventeen-year-old Linda’s romantic fantasy regarding the Prince of Wales.3

Unfortunately I know full well the statistics about how women tend to lose out economically in heterosexual partnerships. Just the other day, inspired by Brandon Taylor’s recent newsletter, a friend and I had an email exchange about how the contemporary novel’s marriage plot has yet to satisfactorily account for the male response to the Ambitious Woman With Plans. We have lots of novels now about the experience of being an Ambitious Woman With Plans, even if the ultimate lesson is that she cannot Have It All, but those novels are not at all moving the needle on men liking the Ambitious Woman. See: the Trad Wife™ and also, uh, Andrew Tate.

Of course, Fanny, though sharp and observant, is not herself Ambitious, and she is apparently happy with her life as a homemaker and mother, and good for her! But Nancy was Ambitious— this was not an irrelevant factor in the breakdown of her marriage with Rodd— and, worse, she still held onto the fantasy. Sometimes reading Nancy’s biography, with all these terrible men floating in and out of her life, makes it sound like sustaining the fantasy that one can have a good heterosexual marriage is more trouble than it was worth.

But the other lesson of The Pursuit of Love is that part of the pursuit is the gifts one picks up along the way. From Fabrice alone, Linda obtains an appartement in Paris, a fur coat, and a French bulldog puppy. This does not sound bad to me. Apparently crying on your suitcase in the Gare du Nord DOES get results. Anybody want to buy me a plane ticket so I can try it out?

In tearing haste,

Diana

But also I don’t believe in spoilers, so I will say it here in the footnotes: Linda dies on the last page, giving birth to Fabrice’s son.

At this time they called each other Susan for no reason either could remember.

This is just a turn of phrase because we must also remember that Linda’s Prince of Wales was David Windsor, which, yikes, and mine is William, Duke of Cambridge, lol???

I am absolutely obsessed with your journey to read all Nancy's novels - I'll admit, Pursuit is the only one I've read so far because I'm basic af, but I recently read the Mary S Lovell biography and I feel like I need to dig deeper!